Executive Summary

How often have you been in a weekly planning meeting when someone is told that they need to start work in an area because the schedule says they should be there? But you know if the site is not ready, it will add unnecessary Work in Process and potentially put the project’s timeline in jeopardy.

All too often, we fall into this habit of operating on this “plan of the day” routine and end up in reactionary mode. This has a significant impact on the productivity of crews, not to mention the cascading effect of how changing plans affect the overall project.

The key is for the team to use Project Production Management principles and practices, such as Takt Planning, to pursue flow on the project.

Based on a Touchplan blog series from industry-leading experts, this deep dive focuses on the foundational science behind Project Production Management and Takt planning.

Through this Deep Dive you will learn to:

- Understand the fundamental principles of PPM in real-world scenarios

- Implement Takt planning on your own projects

- Counteract variation in the rate of performing work by establishing a fixed pace

- Use several countermeasures and practices to minimize variation and the effect on our jobsite performance

- Use the power of Lean Construction principles to identify often overlooked risks that jeopardize the delivery of projects

- Build successful teams to complete construction projects more efficiently

- Build superior project outcomes and profitability

We would like to thank the many authors that contributed to this e-book including George Hunt, Hal Macomber, Terri Erickson, Colin Milberg, and Adam Hoots.

“Changes will happen in construction… The genius of the system is that Takt stabilizes everything on the project so changes that occur in specific locations can be isolated and focused on with Last Planner® or Scrum. What we want is to reduce unneeded variation so we can properly deal with any necessary variation from the owner, adjust Takt zones or Takt trains.”

– Jason Schroeder, author of Elevating Construction Takt Planning

Chapter 1: Flow Provides Focus for Project Production Management

Project Production Management (PPM) is not a subject taught in most construction management courses, although it should be. The fundamentals of PPM are more closely aligned to the reality of projects and the risks associated with them than the more conventional project management thinking. Understanding PPM can help teams effectively identify often overlooked risks that put the delivery of projects in jeopardy.

The Lean Construction Institute (LCI) was initially a DBA (doing business as) name for The Center for Innovation in Project and Production Management. Going back to 1993, PPM has focused on the International Group for Lean Construction (IGLC) and LCI. The Last Planner System of Production Control® is the comprehensive PPM system for design and construction practiced today. The other prevalent approaches are the Critical Path Method (CPM) for project scheduling and control and Advanced Work Packaging (AWP) for planning, designing, and controlling functional blocks (or chunks) of project scope.

Takt Planning and Management has been an underutilized practice for pursuing flow for the production of design and construction work products. Takt has been in practice since 1999 when it was implemented by The Neenan Company. Yet, the first book on Takt for construction was published in March 2021 by Jason Schroeder. In his book, Elevate Construction Takt Planning, Schroeder shares what he learned in the last nine years he’s been experimenting with Takt.

In this e-book, George Hunt and Hal Macomber, along with subject matter expert collaborators, will explain the fundamental principles of PPM in real-world scenarios. It will highlight the power that pursuing flow has for project outcomes, profitability, and team health. It will also demonstrate how Takt will change everything you do on your projects. And you’ll learn how to make it happen.

Chapter 2: Beware of Variation Compounds with Dependence

Variation is present in things we do every day. Variation has a significant impact on our daily lives, from changing driving speeds on the highway leading to traffic jams to the unforeseen weather conditions causing us to delay our planned concrete placement. More specific to our projects, unmanaged variation leads to delays, blown estimates, unsafe conditions, and loads of frustration. Understanding why variation is a big deal, how it affects our projects, and how to counteract it can ultimately lead to more positive project outcomes.

We learned three critical lessons about Project Production Management (PPM) from Toyota that directly relate to our design and construction work.

- Ensure that the production process is not overburdened. Don’t carry a load more than you can handle; don’t run a process longer than the design parameters; don’t cram work into a time shorter than is needed. That’s overburdening.

- Variation must be observed and managed, or it will compound. Tolerances stack; early and late completions don’t offset each other, and variation compounds with dependence.

- Identify and remove waste in our processes. This process requires understanding what adds “value.” Everything else is waste from the customer’s perspective.

The order of these lessons matters. While we didn’t know that when we learned these lessons, we do now. Many companies who were serious about Lean attacked waste first. Why? Reducing waste meant decreased costs and reduced time through production. Unfortunately, working on waste before taking care of the first two items isn’t sustainable.

First, a few words about overburdening: DON’T DO IT.

It’s dangerous for a 10-ton crane to attempt to lift 15 tons. Don’t do it. It’s dangerous for people to work in the hot sun without adequate hydration. Don’t do it. People working long hours cause undetected errors regularly. Don’t do it. Ensure that people, processes, and equipment are right-sized for the work that needs to be done.

What’s The Big Deal About Variation?

We’ll start with our commonsense. Which of the following actions are suitable for your project?

- Let’s get a jump on it

- We want supers who are pushers

- Give us plenty of laydown space

- Make sure that all planned activities start on time

- Stop starting. Start finishing

- Supers adjust to the changing circumstances

- Will run the project as if no laydown space is available

- Adjust to the changing circumstances of the project

Our commonsense or common practice often produces precisely the opposite of what we want. For instance, on critical path-managed projects, teams focus on starting every activity as planned. This practice often leads to excess work in process and, therefore, a late project. (We’ll cover this in detail in an upcoming post.) The right-side options from the above list produce better outcomes. We have to change our commonsense to get the most from PPM.

Those of you who have played the Lean Construction Institute’s Parade of Trades® simulation have experienced operations that are dependent on the output of prior ones; any gains in the upstream operations are lost. In addition, those losses accumulate for downstream operations on an exponential basis. The larger the variation, the more variation compounds. Try a thought experiment with me.

We have a simple three-operation sequence of work. Each crew works at the same average pace of six units per day. It will take them five days on average each to complete their work for the 30 units. Each operation starts one day after the preceding operation.

- Day one: 1st operation does 5 units

- Day two: 2nd operation does 4 units and 1st operation does 7 units

- Day three: 3rd operation does 4 units; 2nd operation does 5 units; 1st operation does 5 units.

This pattern continues for an expected nine days. All crews are prepared to do all of their six units, however except for the 1st operation, the other operations can’t do more than the work that is ready for them regardless of how efficient the crews are. Upstream gains are lost, and losses accumulate. We can predict that work will not finish by day nine, and we don’t know when it will end. How would this work out in a 25 operation sequence of work for 100 units? Yes, it’s unpredictable. Most of the time, it’s so unreliable that we routinely buffer our estimates for how long the project will take.

“If managers can find ways to support everyday progress… they can actually accomplish dual goals of supporting superb employee well-being at the same time they’re supporting the success of their companies.”

– Teresa Amabile, co-author of The Progress Principle

What Can We Do To Counteract Variation?

We have several countermeasures or practices available to minimize variation and the effect on our performance.

- Make the work ready for the people and the people ready for the work. The Make Ready process entails a rigorous evaluation of any roadblock or hurdle that could keep work from starting and finishing. We call these constraints. The purpose of look-ahead planning is to surface and resolve limitations so there is no impediment to doing the work that we agreed we should be doing.

- A great way to counteract variation in the rate of performing work is to establish a fixed pace. Lean construction adopted the German word for this — Takt. Set a pace that every operation in a sequence will work. Establish swing capacity (buffer) so that work can usually/always be done as planned. Maintain available alternative work (workable backlog) for that swing capacity, so they are always productive.

- Use interim milestones so the collection of crews can see that they are “making the pace” (A concept explained in The Progress Principle by Teresa Amabile and Steven Kramer)

- Every week make reliable promises from one trade to the others based on having the capacity and material to do the work they promise.

- Learn from the variation that you experience. Status the work daily, including the reasons for variation. Use five whys to understand the underlying cause(s) of the variation. Take countermeasures to improve it.

Reducing variation on your project is one of the best ways to get the outcomes you want. It’s not as difficult as you may think. It starts by making a shift in common practice coupled with the above five practices. Skeptical? Try it!

Chapter 3: Bottlenecks Rule — Make it the Policy

All processes and projects have bottlenecks or constraints. A physical bottleneck determines the maximum rate at which the process flows. Increasing the size of a bottle without changing the size of the bottleneck has no impact on flow. Yet, our everyday experience of bottlenecks can be one of surprise, dismay, or frustration. Let’s shift our relationship to them by taking charge of the bottlenecks.

Understanding the Theory of Constraints

Eli Goldratt’s work on the Theory of Constraints (ToC) was made famous by his book, The Goal, An Ongoing Process of Improvement, first published in 1982. The Goal and ToC were critical to the development of the theory and practice of Lean Construction. Greg Howell discovered the book in the 1990s. His inspiration was the story of the boy scout hike and campfire lesson to create the Parade of Trades® simulation, the essential way people in the construction industry learn about constraints, variation, and compounding effects in project-based production systems.

Clarke Ching, a serious Goldratt student and Agile project expert, has been writing to make Goldratt’s lessons more available and understandable to a larger audience. His book, The Bottleneck Rules: How to Get More Done (When Working Harder isn’t Working), is used in study-action teams in the design and construction industry.

“When you see your first bottleneck, it will hit you like a good movie plot twist does, and you will wonder, ‘How on earth did I not see that until now?’ You’ll shake your head in disbelief when you realize that something so seemingly harmless has been sitting there, in plain sight, sucking the life out of your workplace and nobody noticed. The good news is that you’re not only going to learn to see bottlenecks — you’ll also learn how to tame them and manage them. Your workplace will speed up and, at the same time, calm down. Taming bottlenecks is easy when you can see them.”

– Clarke Ching, author of The Bottleneck Rules

Use Bottlenecks for the Benefit of Project Production Systems

Project-based production systems are often short-lived. Pull planning is one common way teams are designing phase plans. Unfortunately, even people who have been introduced to Lean Construction, pull planning, and the realities of bottlenecks don’t often explicitly consider what operation (activity) will limit or control production flow, let alone strategically locate the control point. Consequently, just out of plain sight, the bottleneck does what it always does – it controls the flow through that phase of work. That might impact the phase milestone, and if it does, firefighting ensues.

Alternatively, let’s make a conscious decision when designing a phase of work to place the bottleneck to help control the flow or throughput of the process. Consider the capacity limitations of each operation. You might find that the pace of the bottleneck is sufficient to support the milestone target. If not, look for alternative means to accomplish the limiting work. Offsite construction, kitting, shift work, etc., may help. Pick a visible operation to set the pace for the phase. That operation’s capacity should match the desired pace. All other trades or workgroups adjust their work and team size to match the desired pace. Remember, the throughput of the whole process can’t be more than the throughput of the bottleneck. Any operation that tries to perform at a higher rate will not result in overall gains for the phase milestone.

It helps to place the pacing operation where there are buffers available. We commonly use two types of buffers on projects — time and capacity buffers. Time buffers, known as “float” in scheduling jargon, are best placed at the end of a phase just before the milestone. Time buffers are consumed when slippages occur. Daily overtime and Saturday work are examples of capacity buffers. While our industry uses these buffers often, it comes with considerable risks and detrimental impacts on the team members. Longer hours often negatively increase safety, quality, and productivity. Worse, families are seriously impacted when mom or dad is repeatedly not available for family responsibilities. Wise leaders do not put the quality of life of “our most important assets” at risk.

The better option is to use standby capacity coupled with a workable backlog when designing the phase production plan – especially with pace-setting bottleneck activities. Standby capacity fills the gap between the average daily capacity needed and the daily spikes and dips in demand. We set that extra capacity for all crews of the same trade. If plumbing is running four crews with 15 people, they might take care of a large percentage of the daily ups and downs as long as flexing happens between the crews. Alternatively, they may plan for one or two additional people for partial days a few days each week — standby capacity. The rest of the time, they are doing work that is ready but not needed until a later time AND will not cause problems for other teams when performed out of sequence, like unpacking product or prefabbing components — workable backlog.

Five Types of Bottlenecks

Clarke Ching distinguishes five usual bottlenecks we encounter on our projects.

- Wild bottlenecks often hide, and they are either unmanaged or poorly managed.

- Tamed bottlenecks don’t have as much capacity as we would like, but they are visible and easily managed.

- A Deliberate bottleneck’s design limits the flow through a system deliberately – e.g., the bottleneck of a wine bottle or a Tabasco sauce bottle.

- Bottles have necks to control the speed of the content as it flows out.

- A simple place to put a deliberate bottleneck is at the start of a process so that we choke, restrict or throttle the flow of work into the system, so the entire system runs at the speed of that control point.

- Right stuff bottlenecks — Are we being effective? Are we working on the right stuff?

- Right place bottlenecks — Are they where they are supposed to be?

Taming the Bottlenecks

Taming bottlenecks is done with the FOCCCUS process (ToC Focusing mechanism). It’s a step-by-step approach for identifying and systematically improving the situation, so the bottleneck is working FOR the process. The steps are Find, Optimize, Coordinate, Collaborate, Curate, Upgrade, and Start again. Learn more from Clarke’s short and very readable book.

Key Takeaways

Remember, you and your team are responsible for designing the production system, which includes strategic placement of the bottleneck. Take that opportunity seriously.

- A bottleneck ALWAYS exists — “not having a bottleneck” is not possible — just because you can’t see your bottleneck doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist

- Do not be a victim of your project’s bottlenecks

- Use bottlenecks as a way to pace the project and control the project

- Place your bottleneck in a location where you maximize buffers available

- There is a probabilistic nature to the whole thing — ACCEPT that there will be times when the bottleneck is working at maximum capacity and other times when it’s not. (more on this later)

- Life still happens — stay on the lookout for previously hidden bottlenecks

- Develop work agreements with your project team so that “bottleneck” activities take priority over other activities.

- These agreements aren’t just about finding the bottleneck; this is about DESIGNING the bottleneck(s)

- Shift language from “bottleneck” to “control points” — bottlenecks lead to victims, control points lead to empowerment. . .

- Develop multiple control points — NEVER have EVERYTHING be a control point. Starting work, bottleneck work and finishing work are great control points.

- Control points should be actively monitored, managed, and improved.

Let’s relentlessly pursue flow by reducing our project team’s experiences of surprise, dismay, and frustration by shifting our relationship with bottlenecks and taking charge of them.

Chapter 4: Delays Increase Exponentially as Utilization Increases

Project teams have a tough job pursuing high productivity for workgroups while maintaining and improving flow on the job. Often in the pursuit to keep all of the resources on-site “busy,” we end up taking actions that hurt the overall project flow and ultimately create more problems. Niklas Modig and Par Ahlstrom do a good job pointing to this paradox in This Is Lean, Resolving the Efficiency Paradox. In short, focusing on flow over utilizing resources makes it possible to free up more resources. For project-based production, the paradox resolves by making work ready for people and people ready for work. Almost. Variation and high resource utilization on our projects combine to make this task difficult for our teams. George and Hal wrote about the compounding of variation with dependence in Chapter 2. In this chapter, we take on how high utilization in the presence of high variation leads to project delays and the actions and countermeasures we can take.

Production Science of Utilization

In the 1960s, Sir John Kingman created an equation that approximates waiting time (delay) as a function of variation, utilization, and processing time. None of us are likely to use the equation in designing and managing a project phase production plan. Knowing how the variables interact, however, is quite important. Understanding the tradeoff between the three can significantly help us design our workflows to give us the results we want.

Consider rush-hour traffic. During that time, there was high utilization of the available and fixed road capacity. We also experience two kinds of variation. We see people driving at different speeds (processing time), leading to other drivers changing lanes (arrival variation). We also see drivers entering and merging with traffic at various intervals (arrival variation). Since there is high dependence among the drivers, the variation compounds those up the road, requiring them to slow down and sometimes stop. The same roadway at a less busy time of day (lower capacity utilization) has far more ability to absorb the processing and arrival variation of the drivers.

It turns out that delay increases exponentially as capacity utilization and variation increase. Highway engineers use various countermeasures to minimize sources of variation. They pace arrivals at on-ramps with stop-and-go lights. They limit movement from the left-most lanes to minimize arrival variation from lane departures. They also post minimum speed limits for the left-most lanes.

Project Production System Implications

We have many sources of variation on our projects that amplify the severity of high utilization:

- Processing time varies from one crew to another as well as within crews.

- Crew sizes may vary from one day to the next as people take time off, get sick, or are assigned to different projects to handle emergent work.

- The workspace and conditions (weather) varies.

- The work itself varies.

- Without attention, the batch size varies.

- The start of work varies from week to week, depending on what the master schedule says.

- Quality varies, requiring rework.

- Material availability varies, requiring go-backs.

- Equipment reliability and availability vary.

Utilization increases as variation increases because the same people who are doing work need to respond to all of the variation. The technical term for this is a “mess.”

What Can We Do?

We can take two kinds of action: reduce sources of variation and adopt countermeasures for high utilization. Depending on the conditions of our projects, we may be able to do one more readily than the other. We aim to keep work flowing while maintaining good productivity. Starting with variation, making work ready for people and people ready for work is essential for eliminating the arrival class of variation. Couple that with making reliable promises [pdf] between trade partners, and the impact of variation can begin to be controlled. High reliability of completions leads to high reliability of starting work as planned. Touchplan Insights helps with both. You see how well you are making work-ready with the constraints performance. And percent promises complete is prominently displayed.

We also need to accommodate system variation. We do this principally with standby capacity coupled with a workable backlog. Standby capacity lets a trade’s crews work at nearly 100% utilization, knowing that the standby workers are ready to stop what they are doing or never start doing something, to be available to crews for part of the day. What are they doing when they are not needed? They are doing work that isn’t needed in the current week but is ready (unconstrained) AND doesn’t create a sequencing problem for the downstream trade, “the customer” of the work. This is called a workable backlog. Workable backlog is identified for each trade every week during their weekly work planning conversation. The trade customer must agree to declare future work as workable, or it doesn’t go on the list.

The last countermeasure is to track units in place as compared to the crew size. This is done on a trade-by-trade basis. They’ll have targets for the promised period. Quickly identifying variances from those targets is essential. Have trades status their work just before or at the end-of-day stand-up meeting in the field. Share any variation that occurred and take necessary follow-up action. Touchplan Go makes it easy to always have up-to-date status.

Making workflow is the senior goal for all production systems. Understanding how high resource utilization relates to variation on our projects and vice versa is a great first step. As the authors of This Is Lean say in the title, there is usually a paradox between flow and resource efficiency. You now know how to resolve that paradox. The time to act is now.

Chapter 5: Bigger Batches Create Longer Projects

Common sense tells us the more work we get started, the sooner we finish. One common practice is to give a framer a whole floor of a building, thinking that makes them more productive. We believe productivity is equivalent to speed. It’s not.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor John Little, Ph.D., created the proof (Little’s Law) that relates time in a system (like the time to complete all steps on a floor) with processing time (like the speed crews complete a floor) and the internal arrival of work (like the amount of floor space started but not finished). The implication for construction is that the more frequently we hand over space from one trade to the next, i.e., the less stagger between trades, the sooner the project will finish.

“It is our moral imperative to design our construction production process to our smallest practical batch sizes. Otherwise, we are squandering our client’s resources. And … we reduce our risk in the process.”

– John Little, Professor Emeritus at the MIT Sloan School of Management

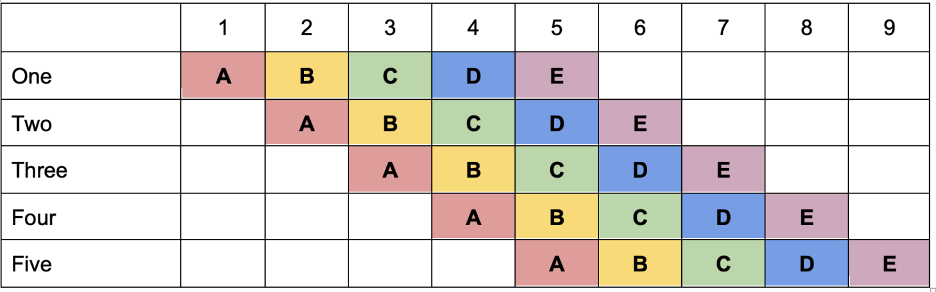

Let’s use a simple example. We have a small project. There are five floors in the building. Five operations need to be completed on each floor by five different trades. Each trade is staffed to do their work on a floor in five days. We’ll start with the situation where each trade hands off a floor each week. The first trade A finishes floor 1 on week one and then moves to floor 2 at the beginning of week two. That makes floor 1 available for trade B on week two. By week five, trade A is working on the fifth floor, and trade E starts on the first floor. Week-by-week, each trade moves up the building finishing their work in five weeks. Trade A finishes in the fifth week. Trade E finishes four weeks later in week nine.

Now let’s consider how long the project would take if we hand over 20% of the floor each day. On day two, the second trade starts, and by day five, all trades are working, which is more than three weeks earlier than the larger handoff or batch approach. When the handoff or batch size is a whole floor, it takes nine weeks. When the batch size is cut to 20% of the floor, it takes 29 days, cutting the time by 35%.

Calculating the Benefit of Small Batch Production

We derive an equation for determining the duration of a phase of work from Little’s Law. In the following equation [ Work In Process] / Throughput = Cycle Time, where: Work In Process is the maximum number of areas or flow units being worked on in a given moment; Throughput is the speed of the crews shown as the number of areas in a batch divided by the time required for a crew to complete the batch, and Cycle Time is the amount of time for all operations to complete one area.

[(Number of Flow Units – Batch Size) + (Number of Operations * Batch Size)] / Throughput = Total Project Duration.

Use Case #1

Let’s use the above example. There are 25 flow units (work areas that can be started and finished). In the first case, a trade does a batch of five flow units before turning over space to another trade. There are five operations (trades) performed on each flow unit. The throughput time (the time the flow unit is in an operation) is 5 flow units in 5 days or 1 unit per day.

One week stagger [(25 – 5)) + (5 * 5)] * 1 / 1 = 45 days

One day stagger [(25 – 1)) + (5 * 1)] * 1 / 1 = 29 days

Savings 16 days, about 35% shorter.

Use Case #2

There is an 18-story university residence hall and alternate floors have different layouts. The work involves interior framing through finishing. There are 26 operations. We propose splitting into two flow units per floor with different layouts, but similar square footage. The GC plans to turn over one floor per week (5 days). We propose to turn over one flow unit (half-floor) every two days. Notice the flow units increase because we made the space smaller.

One week stagger [(18 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 5 / 1 = 215 days

Two day stagger [(36 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 2 / 1 = 122 days

Savings: 93 days, about 43% shorter.

Let’s consider going smaller, then smaller again. First ¼ of a floor, then ⅛.

One day stagger [(72 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 1 / 1 = 97 days (doubled the flow units)

Savings: 25 days, about 20% shorter.

Half day stagger [(144 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 0.5 / 1 = 84.5 days (doubled the flow units, again)

Savings: 12.5 days, about 13% shorter.

Quarter day stagger [(288 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 0.25 / 1 = 78.5 days (doubled the flow units, again)

Savings: 6 days, about 7% shorter.

The time savings from the change in batching from 18 flow units to 288 flow units resulted in savings from 215 days to 78.5 days. A whopping 63% reduction in the cycle time.

Think about this.

How much money can we save for our clients when we significantly reduce project durations?

How much revenue or value can we produce for our clients when we deliver projects earlier?

It is our moral imperative to design our construction production process to our smallest practical batch sizes. Otherwise, we are squandering our client’s resources. And, we reduce our risk in the process.

Implications for Phase Planning

Projects take more time the more extensive the batch of work in a physical area that is exclusively assigned. Cut the batch size, and the project will get shorter as long as the workflows are without interruption from one trade to the next. Notice there is a diminishing return as you continue to cut batch size.

Use a rule of thumb to start with a batch size that can be done reliably by all trades in one day. Scale up the number of flow units from that if necessary to accommodate crew sizing. We’ll cover more on this in upcoming chapters.

Not only are projects shorter with small batches, but quality, safety, and workplace cleanliness improve. Of course, all of this depends on being able to execute the plan. Initially, there will be bumps in the road. Commit yourselves to learn from mistakes, and the project will get better fast.

Chapter 6: Flow When You Can — Pull When You Can’t — Stop Pushing

“Changes will happen in construction… The genius of the system is that Takt stabilizes everything on the project so changes that occur in specific locations can be isolated and focused on with Last Planner® or Scrum. What we want is to reduce unneeded variation so we can properly deal with any necessary variation from the owner, adjust Takt zones or Takt trains.”

– Jason Schroeder, author of Elevate Construction Takt Planning

Up to this point, we have explored the principles or laws that universally govern production systems. Neither the construction industry nor associated academia introduce, let alone teach, production system design and management. Consequently, we rely on the experience and good judgment of successful senior people to guide the way. Typically these are the hard lessons that the most successful builders have “learned by experience.” These production laws are the keys to establishing flow on a project.

So, how did we learn about Project Production Management? It started with a fellowship for a young academic visiting Stanford in 1992. Lauri Koskela, now Professor of Construction and Project Management, noticed what was happening in Freemont, California at NUMMI, a partnership between Toyota and GM. He wrote the first paper that proposed the “new production principles” applied to design and construction. A year later, academics from several universities convened for the first annual International Group for Lean Construction.

The Lean Construction Institute provided guidance through many books on Toyota and other Lean companies. But, unfortunately, the construction industry also misunderstood some concepts. Let’s take the five Lean thinking principles as an example. Jim Womack and Dan Jones proposed that we could be Lean if we adopted these principles:

- Define value from the customer’s perspective and in their language

- Organize the value-adding work as a value stream

- Make the workflow

- Pull work through the value stream

- Pursue perfection

What Jim and Dan underplayed, and many of us failed to understand, is that all five principles must be operating. Yes, we intend to design production systems to deliver what we promise our customers. And then it breaks down. Whether we describe the physical work of construction or the intangible work of architecture and engineering, we spend far too little time exploring the value stream for the senior promises we make to the customer (client). Flow turns out to be the goal of the production system, not just one of the principles. That is a big misunderstanding. Flow when you can; pull when you can’t. Yet, our practice of customarily pushing work into the system makes flow unlikely. Stop pushing. And perfection? We won’t get the production system design right, but we can be better every day ONLY IF we embrace learning and experimentation as our practice.

Womack and Jones failed to show that the whole system must change. Tinkering around at the edges has little to no impact. Sampling from the Lean buffet of tools, methods, and practices might make you feel good, but results are insignificant. We will only achieve the benefits of production system design when we start with the purpose of the system. Flow is the goal of all production systems. But, it is only possible when the production system conforms to the four basic production laws. And, that is not enough. We must replace many of our current practices with new practices to operate in accord with those laws.

You understand from chapter two that variation in operations performance compounds (exponentially) with dependency.

In the third chapter, we explained that no improvement anywhere in the system improves throughput unless we expand the bottleneck.

The fourth chapter illustrated how operating a production system to high utilization levels significantly delays project completion.

In the fifth chapter, we find projects are surprisingly shorter when we embrace small-batch construction.

These are the laws of production. Yet, what do we do on an everyday basis? We often act by following critical path thinking. In other words, we ignore, do not understand, or are oblivious to production laws.

Stop pushing doesn’t mean to stop encouraging people to go further. Instead, in production management, pushing means starting work on a flow unit without regard for the availability of resources to continue to work on that flow unit. Doing work when it isn’t required is also considered pushing. Taking people away from work in-process interrupts flow and increases variation. Working ahead unnecessarily takes on more risk. Either case of pushing is terrible for the project.

As a consultant on a nuclear power plant upgrade project, Hal Macomer was fired because he advised the team to throttle back starting work (contrary to the master schedule) while increasing the system’s throughput. Why? The project wasn’t meeting the planned start dates in the master schedule. The work was not ready to do it. The capacity wasn’t available to do it. Yet, the commonsense among the scheduling community governed managing the project. The result? The project fell further behind when they went back to launching work according to planned start dates.

Don’t mess with production laws. You will not win.

Chapter 7: Pace Construction to Bring Sanity to Your Construction Project

We’ve learned not to ignore production laws when we plan our projects. There is one approach that we should all be starting with as we plan. It’s Takt, a German word borrowed by the Japanese, meaning beat, rhythm, or pace. The intent is to establish a consistent rate for performing all operations for a work phase. Ideally, the speed is set based on the desired milestone completion for the phase and project.

Pacing production brings the four production laws together.

- A constant pace removes variation.

- We set the pace based on the smallest practical batch of work.

- The bottleneck operation(s) will control the pace.

- We avoid delays resulting from high capacity utilization and variation.

Pacing production has been a central idea in the Lean construction community since 1999 when Dr. Iris D. Tommelein, Director of the Project Production Systems Laboratory, UC Berkeley, authored a white paper for the Lean Construction Institute titled, “Discrete-event Simulation of Lean Construction Processes.”

In February 2020, at the annual Design Forum, Iris declared:

“Takt planning applies to all projects. No exceptions including non-repetitive (sequential) work.”

– Dr. Iris D. Tommelein, Director of the Project Production Systems Laboratory, UC Berkeley

Experts haven’t seen any evidence to hint at an exception to Dr. Tommelein’s rule. Furthermore, Takt, under different names, has been used at least as far back as the construction of the Empire State Building, which only took 13½ months to complete.

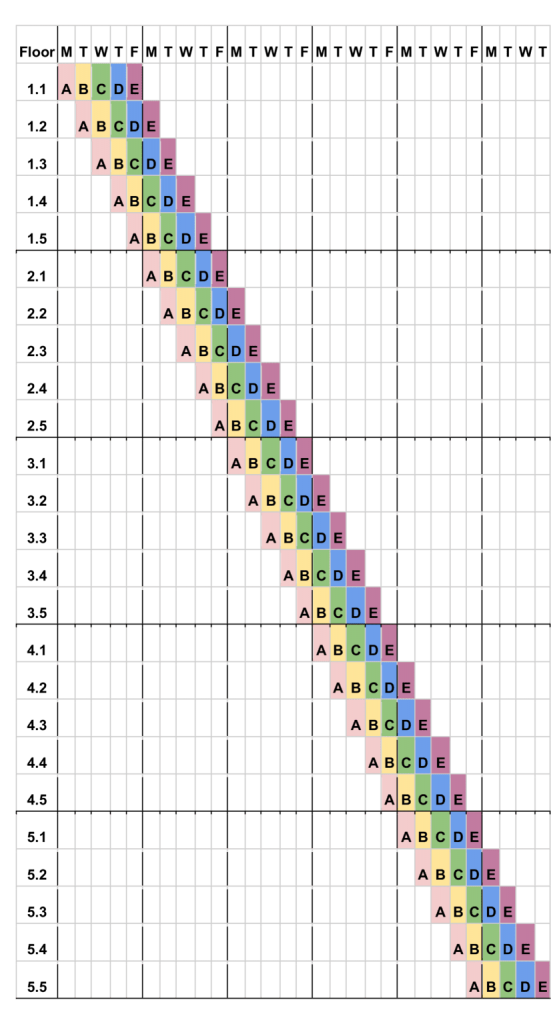

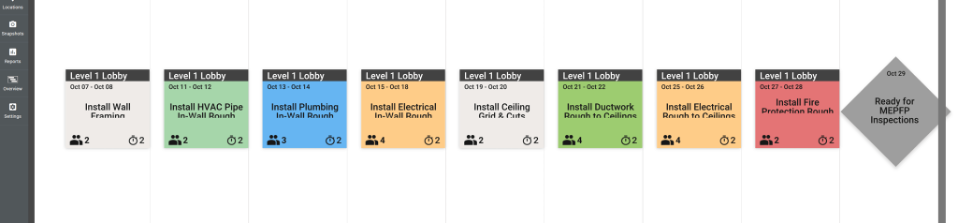

As we explore Takt in-depth in the next chapters, Takt plans look like this:

Notice the stair-step approach. When setting the Takt time (pace), we start with one day to get the shortest phase plan. One day may not be possible for all operations in a phase plan without making accommodations. For example, teams may need to examine the steps in their process to determine if they are value-adding and necessary to perform at the installation location. All other work steps are candidates for moving offline.

For instance:

- Don’t unpackage material at the work site if someone could do that beforehand.

- Don’t mobilize and demobilize tools and materials if they can be on a cart that moves with the workers as they go from one flow unit to another.

- Don’t measure, cut, assemble and coat in the workspace if that could be moved offsite.

The aim for achieving flow is to install, install, and install. Remember, this matters most for those operations that exceed the desired Takt — the bottlenecks.

The usual ways trades work may not be conducive to a consistent short Takt. The way we contract the trades contributes to that. While balanced work is essential, we often contract with one trade without considering the desired paces of the work phases. Remember that flow is our goal.

Chapter 8: Use Non-Repetitive Work for Your First Takt Plan

Using non-repetitive work as our first takt plan may not seem like the obvious path forward, but we believe that it will help you become better at the process in a shorter time. If the work is different for each area (non-repetitive), you will need to build multiple takt plans, giving you the opportunity to learn and improve each time.

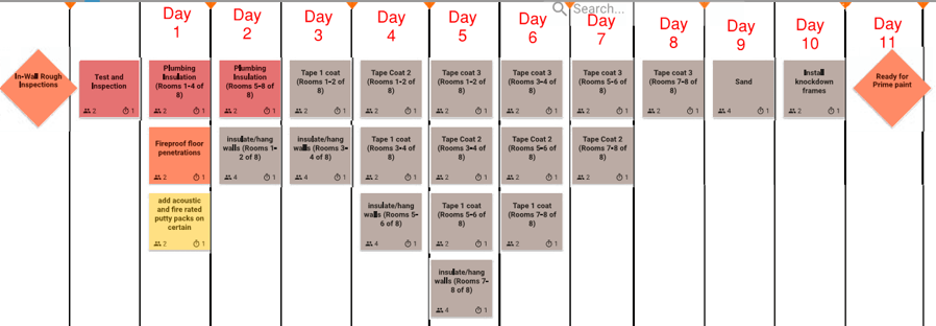

To develop a Takt plan for non-repetitive work (repetitive work has more challenges), you need a typical pattern that gathers information about the sequence of operations, durations, crew sizes, and batch size.

Sequence the Work to Understand the Range of Trade Capabilities

We start by learning what it will take to meet the milestone for a particular phase of work. It will be different for different trades. We design the initial planning to uncover the obstacles to achieving flow.

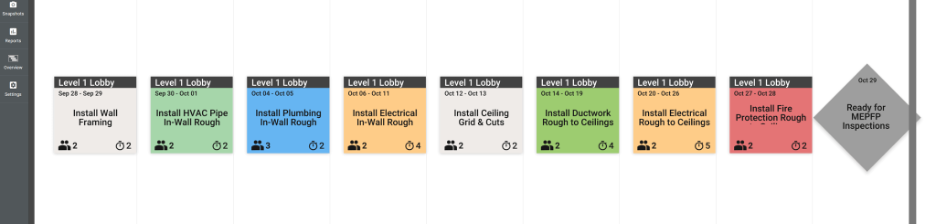

- Identify the milestone conditions of satisfaction — doneness criteria — for the area or location of the work. This area or location should be one of the non-recurring spaces on the project (i.e., lobby, common space)

- Start from the intended completion date and work backward as we do with pull plans.

- For every operation, have the trade partners identify on a work ticket.

- The specific process they will perform

- The smallest crew size that is reasonable

- The minimum duration they need for the operation (smaller is better)

You now have a description of the flow of work and the range of crew sizes and durations the trade partners think they need.

Time to Establish a Takt and Scale Capacities

- Find the smallest crew that can complete the most work in the least amount of time or the operation that will be the bottleneck for the area.

- Scale the other crews to match the Takt (pace) of the fastest smallest crew or bottleneck.

Undoubtedly, when you scale up, you won’t get round numbers. A trade that needed just under three people to do work in two days may need 5.33 people to do it in one day. Taking longer doesn’t meet Takt. Rounding up capacity makes the trade less productive. Neither is acceptable. So, what do we do?

Balance and Buffer the Work

- Find the imbalances. The rule of thumb is to round up the capacity. However, you could look for an improvement that would unload the onsite work to prefabrication, kitting, or operations improvements to reduce the capacity requirements to meet the pace.

- Identify workable backlog (ready but not currently needed work that won’t create problems for other trades when performed early) for partial crew members to work on while others complete the Takt period’s work.

You now have the plan for one non-repeating flow unit that will maintain flow without negatively impacting trade partner productivity.

Install Practices to Maintain Control

“Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans.”

– John Lennon, Beautiful Boy, quoting Allen Sanders, Reader’s Digest, 1957

Takt requires commitments from all trade partners to their “customers,” other trade partners who follow their work, to get the job done in the established Takt. There’s no learning curve on an operation-by-operation basis for non-repetitive work. Get it done, else the following trade may have no place to work. Making work-ready and managing your promises are the essential practices for achieving and sustaining flow.

We make work-ready when we remove all the roadblocks to starting and finishing work as promised. That includes having the resources — tools, equipment, material, skilled team members, and safe working conditions — to perform the work as planned. Still, life — unexpected circumstances and variation — will appear.

So, have an end-of-day stand-up meeting among the last planners (usually foremen) for the operations underway. At that meeting, the last planners report complete to their “customers.” They recommit to their following promises. They ask for help and offer help to keep the flow going. And when that is not possible, they replan the work

Takt is a Journey of Learning

There are a few keys to succeeding with Takt.

- Follow the four production laws (from chapters 2,3,4 and 5).

- Status the work on a timely basis.

- Take care of your “customer” while you take care of yourself.

- Use performance data to improve your planning practices.

- Embrace a mood for learning.

Takt looks like an advanced practice for some people. It’s been around for almost 100 years. While CPM got the attention of the industry rather than Takt, there is no better way to design production consistent with production laws than to use Takt. Additionally, use the Last Planner System of Production Control® to pull it together as a coherent system.

Chapter 9: Approaching Construction TAKTfully

It is essential when talking specifically about Takt planning to realize that the idea of planning production to a set pace is not a new concept in construction. The Empire State Building, for example, was constructed using a schedule that closely resembles a “Line of Balance” schedule, outlining the pace that was necessary for on-site activities as well as fabrication and design. The success of pacing production was demonstrated back in 1930.

In the last chapter, we walked through the basic steps to develop a Takt plan. Now, we will look at some of the nuances and unique scenarios that arise when Takt planning in construction.

Defining the Standard TAKT Unit and Relevant Terms

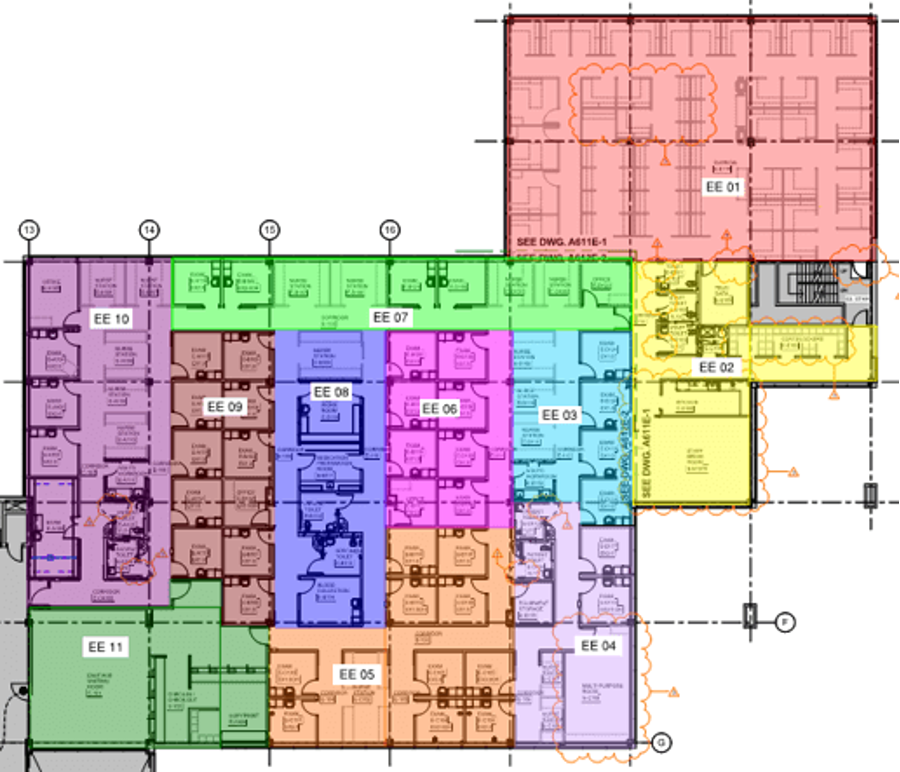

To measure the flow of our construction projects, we look at the work a little differently. This includes the standard units that we use to measure how well the work is flowing. Aside from the difference in units, several other key terms help us better understand how we are looking at our work.

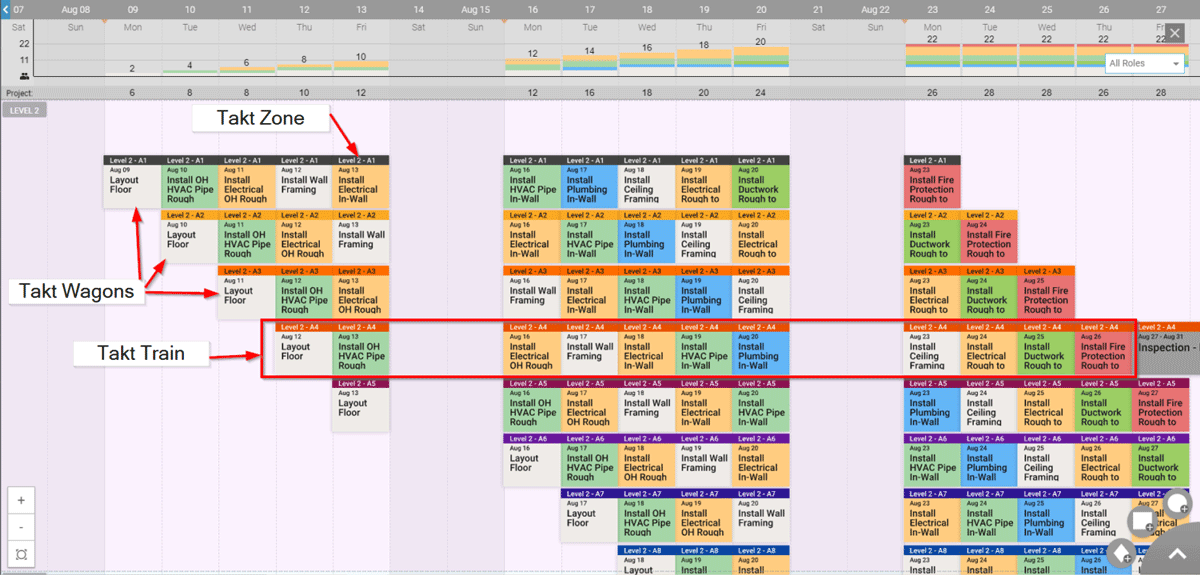

- Takt Zones – The standard areas of production that we define to provide the geographic location of the work. The idea is that the trades will move through these zones at the same pace.

- Takt Wagons – These are the standard flow units in Takt. A wagon consists of a specific scope of work to be done within the given amount of time (Takt time).

- Takt Trains – These are the series of Takt wagons that will flow through a given Takt Zone

Takt Time – This is the amount of time we use to set our beat or pace on the job. This is the standard duration that each Takt wagon has. For example, in a three-day Takt, each wagon will consist of a scope of work done within three days.

Use Buffers to Combat Variation in Construction

On our construction projects, we know that things will happen that will affect our work and cause us to replan. That is where buffers come in. Buffers are strategically placed within our process to combat the inevitable variation on our jobs and keep the overall flow.

- Time Buffers – Extra time added to the process to account for possible variation and keep the Takt trains aligned.

- Inventory Buffers – Extra material or WIP (Work-in-process) maintained to accommodate variation in supply or workload.

- Capacity Buffers – Extra capacity that is carried (additional workforce) to respond to a variation in production. Workable backlog can also be used as a capacity buffer.

Takt Complements Last Planner System®

For those already using the Last Planner System of Production Control® , Takt can work in a very complementary fashion. In the last chapter, we mentioned how teams can hold pull planning sessions to build out the sequence of work and establish what each trade thinks they need for crew size and duration. This information is critical to size Takt zones and level out the Takt wagons properly.

The make-ready process is one of the most critical when it comes to Takt. To keep the continual flow as planned, we need to make sure that there are no roadblocks or constraints that would prevent the team from starting or completing work. Ensuring crews, material, information, and the workspace are ready can mean the difference between continual flow and having to stop and replan work.

Keeping the commitments made in your weekly work plan meetings is another essential part of having continual flow. Your daily standup meetings continue to serve as the check-in for all of the last planners to report on any variances in planned work and help each other keep the flow moving day after day.

So Why Use Takt In Construction?

Considering the four production laws from Chapter 7, Takt planning is an efficient approach to building reliable plans that can produce amazing results on our construction projects.

Chapter 10: Occupied Construction – Moving In with Takt

Those who have completed projects in an occupied setting understand that they come with their own unique set of challenges. As we discussed in the last chapter, Takt has been used successfully on construction projects in general, including occupied settings. While Takt is an excellent way to combat some of the impacts that these challenges bring, we want to present some additional considerations to consider when using Takt in an occupied setting. We’ll also be referencing a relevant completed project that George was on for some context.

Handling the Usual Suspects

An obvious challenge in an occupied setting is working around the tenants of the building. We have to keep everything separate enough, but also keep those in the buildings safe and as undisturbed as possible. This scenario requires clear, concise communication about where and when activities are taking place and what types of restrictions will be required. Because Takt is on a regular rhythm, workflow becomes more predictable, making it easier to communicate where and when things happen.

In the Lahey GIM project example, two wings were being worked on simultaneously with tenants on the floor below. Based on the one-day Takt that was set, a detailed plan was given to the downstairs neighbors, noting exactly which areas needed to be blocked off for plumbing tie-ins. While this event brought some disruption, confidence in the Takt plan allowed for the least amount possible.

New Considerations

Nevertheless, there are still challenges with occupied construction that we need to consider when designing our Takt plans. These projects will inevitably bring more unknowns and variation, translating to more ways to derail plans.

On the Lahey project, we planned and got permission for sectioning an area off to core holes during the day. Once the work started, it became apparent that the noise was too disruptive, so that operation needed to be moved to off-hours. This caused us to need to re-plan so that coring at night didn’t create a new problem for the dependent operations during the day.

Teams must make sure their plans are robust enough to withstand the variation that will occur. This means implementing strategic time, capacity, and/or inventory buffers for when things happen, and we need to change course.

With Lahey, floor areas were designated as workable backlog to act as a capacity buffer for when trades finished early or as a fall-back if work in an area needed to be paused. The plan allowed workers on-site to remain productive and continue to add direct value to the project by accounting for variation.

As long as we account for the additional challenges of occupied construction, Takt is a great way to minimize impacts that happen to our job and the disruption to the occupants—it’s mutually beneficial.

Chapter 11: Turning Around a Project with Takt

We have all been there. Despite the best intentions from the whole team, our project experiences delays and ends up way behind schedule. There are several countermeasures that we usually deploy in these situations to try and turn the project around and finish on time. In this chapter, we are going to discuss why Takt should be used as a countermeasure, some tips for success, and some examples of a couple of projects (one healthcare and one dormitory project) that used Takt to turn around a late project and bring it in on time.

Why use Takt on a Project Turnaround?

You know that the atmosphere can be tense for anyone who has worked on a project that is significantly behind schedule. The normal ways of doing things are not working, everyone is putting in loads of overtime, and the schedule seems to keep slipping. Something needs to be changed, or the spiral downward will continue.

We know from previous chapters that using Takt can bring stability to the project and make planning more predictable. On both the healthcare and dormitory projects, tensions were high as they were trending six weeks behind schedule. In both scenarios, the teams enlisted outside help to implement Takt planning.

Suspend Thought and Be Open to Change

To be successful in this type of situation, the team needs to put any preconceived notions they have behind them and be open to change. For most of our projects, the consequences of being late can be enough to convince the team that they need to try something different.

In the case of the healthcare project, the patient rooms that were being built would be the space for a whole new group of hired surgeons. If there was no space for them to go, there was a risk that they would seek employment elsewhere. On the dormitory project, the building had already started to be rented out to other universities in the area. If the building were not done, they would need to find alternate housing for students. Both projects decided that finishing late was not an option and decided to make a change.

Be OK with Not Getting it Right the First Time

Planning is all about making the most educated guess at the time. Inevitably, this means that we will be wrong on some of our projections and require adjustments, particularly when a new process and way of thinking are being learned. Working in specific buffers to the Takt plan can help account for some of this so that there will be minimal impact to the overall flow.

On the dormitory project, the team ran into several planned durations that ended up being off. They could see this quickly and adjust for the other areas before it became a more significant problem based on the small batch sizes. They also used Saturdays as an extra capacity buffer. If activities were not finished during the week as planned, trades would use Saturday to catch up to maintain flow.

Takt Will Be Doable But Not Always Easy

Implementing Takt in the middle of a project will also need to be done with some flexibility. While we may want to approach everything “by the book,” we need to acknowledge that the current circumstances may make things a little more difficult as the project was not originally planned for Takt. Current logistics of the project, capabilities of the team, and general project location may all limit how we can fully implement the new process to its full potential.

For example, on the healthcare project, the team decided that they would prefabricate the headwalls and only install them as a single unit to speed up the process on-site. The problem was that the electricians did not have the setup to be able to prefabricate offsite. Ultimately, the team prefabricated most of the headwall and installed the rest in place.

While it may seem like a stretch at first, implementing Takt to turn a project around has and can be done with great success. Always keeping the production laws in mind and continuously adjusting the plan are essential if the team is to succeed.

Chapter 12: Coupling Learning with Takt

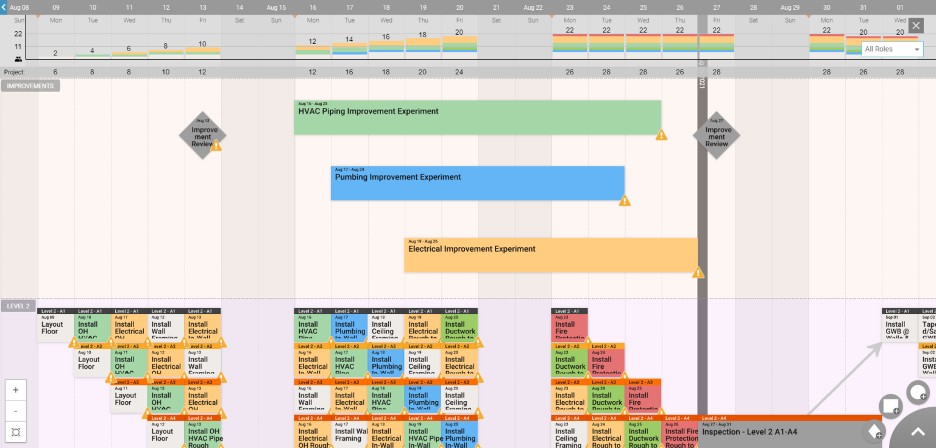

Throughout this e-book, we have discussed several ways Takt can be utilized to structure our work and bring great results to our projects. While implementing Takt alone offers enormous benefits, coupling it with structured improvement cycles (deliberate experimentation) can elevate it to the next level. Many teams talk about continuous improvement, but often they are more sporadic in practice. If done alongside our regular Takt planning, it can give us the structure needed to develop lasting habits that won’t fall by the wayside.

Establish a Cadence of Formal Reviews

Building in a cadence to review progress is essential for keeping everyone engaged. Since the work on-site is already being planned to a regular Takt time, it should be easy to prepare for experimentation and check-ins.

Creating a swimlane in Touchplan specifically for improvements can keep these activities at the forefront of everyone’s minds. If we review the improvement activities and our usual work, we start to understand that our work and improvement are one and the same. This can be key to sustaining ongoing improvements throughout a project.

Establish An Improvement Agenda

Understanding what is valued by the team is an important step to ensuring clear direction and improvement towards the desired goal. With Takt, an obvious goal would be continuous flow. Maybe the team also wants to have a project with zero punch list items at the end of the job. Whatever the overall goals are, they will drive the direction of our improvements as well as the interim steps that need to be taken to reach them.

Experiment Towards Better In The Way Of The Toyota Kata

Without getting into too much detail on exactly what the Toyota Kata is, in a nutshell, it incorporates a structured and focused approach to create a continuous learning and improvement culture. This falls in line with what we have talked about in the previous sections.

It is important to note that the emphasis is put on doing small, incremental “experiments” that bring us closer to the next goal. While we learn and adjust, we keep the change small to avoid a larger-scale disruption to our productivity that a more significant change brings. This limits impact and gives us feedback sooner.

While many of us try to practice continuous improvement, it can often turn into something that falls off after some time. By coupling the idea of improvement cycles with our Takt planning, we can add a structured learning program to our projects, resulting in an amazing jobsite culture and enhancing positive results.

Chapter 13: Takt for Professional Services

While this series has focused primarily on Takt in construction so far, we wanted to be sure to discuss how those in the professional services can use it as well. Pacing the production of design can have similar benefits to those described for construction. A regular cadence of information handoffs between disciplines creates a steady and reliable plan that can help hold on to those precious budgeted hours.

Re-define Deliverables

As we discussed in a previous chapter, the work on a job is broken into a series of Takt wagons that make up a series of Takt trains, which make their way through the different Takt zones that have been defined. We run into the problem that design cycles are not typically thought about by geographic location or as linear. It is thought about as a system, i.e., structural, electrical, plumbing, etc.

The team will need to determine how to break down the overall scope into smaller batches (chunks) to be handed off at the end of each Takt interval. This will require the identification of dependencies and what workflows can be running concurrently. Ultimately, discussion and planning are what create the work packages that fit into each Takt wagon.

Properly Size Your Deliverables

When sizing and balancing the deliverables, it will be important for everyone to take the time to honestly assess how much effort is required to complete the work within the scheduled Takt time. Negotiating the level of detail expected in each work package can prevent the team from over-producing or over-processing (i.e., “waste”). Identifying and negotiating the conditions of satisfaction for the handoff will ensure that the deliverable has the appropriate amount of scope without overburdening the resources. The idea here is to “pull” deliverables based on a request by the downstream designer or other “customer.”

Keep a Regular Feedback Loop

A regular team standup meeting is one of the best ways for teams to stay on the same page. Adjustments that are needed to the Takt plan will be discussed in these meetings. To make them successful, the team should agree on a good set of rules to follow while in these meetings. Teams familiar with Scrum or Kanban will already have a solid set of tools to navigate and manage the discussions. This meeting also reduces the number of unexpected touchpoints between team members and allows for more reliable and transparent communication flows.

While usually talked about with construction, Takt can also be used as an effective way to pace the production of our design. Coupling it with other tools such as Scrum or Kanban can help manage and identify where the plan needs to be adjusted and how the team can better balance the workflow.

Chapter 14: Transition from Responsibility to Accountability with Takt Planning

We have established a background on Project Production Management, Takt planning, and several examples of how these concepts can be used to vastly improve your project results. The examples serve as a solid foundation for taking responsibility for your scheduling process utilizing Takt planning. From this point forward, we will focus on how to take accountability for executing the Takt plan. There are many rules and best practices and others that are being established in real-time, but it is vital to focus on the most important ones, not to be all-inclusive.

Benchmark First Work in Place to Avoid Repeating Mistakes

Nothing will ruin the flow of your jobsite more than having to go back, rip out installed work, and reinstall a defective installation. This becomes amplified the longer time passes with the faulty items built on top of it. There are several ways that Touchplan teams have been able to avoid “go-back work.”

- Understand prescriptive and descriptive expectations from all stakeholders

- Conceptual Mock-ups away from building

- Material receipt inspection

- First in place mock-up and inspection by all stakeholders

- Prescriptive and descriptive continuous inspection walks with all stakeholders

When all appropriate parties review and approve each of these opportunities for disruption, corrections can be made before the remainder of work is put in place. After this initial approval, both prescriptive and descriptive expectations will be mutually agreed upon, minimizing the need to redo the same work in other areas. As we bring the prescriptive and descriptive requirements to the surface, Touchplan teams can begin cautiously building to confirm their understanding of the expectations. Conceptual mock-ups are typically done away from the building and are the first step in the building process. Once the team agrees the mock-up is acceptable, the transition to the jobsite begins, and the team does another in-place mock-up to ensure repeatability. Once the team is aligned in the field, the building starts. As the building progresses, the teams involve all stakeholders with continuous prescriptive and descriptive inspections throughout the building.

Install But Never Assemble in Place, Fabricate, or Coat

It is becoming more commonplace to see jobs utilize offsite prefabrication, but it is still far from being the norm. If you are planning on using Takt, prefabrication will be a game-changer. When you move multiple steps involving raw materials and assembly from the jobsite, teams only need to install in-place. Depending on the operation, the time required on the site decreases significantly. It could mean that one trade could shift from being the bottleneck that extends the overall Takt time to be faster, all with reduced overall Takt time. Prefabrication takes many steps that introduce variation and move them to a controlled environment that will not affect the work on site. Do you remember Herbie from the Goal? Herbie moved much faster once his team took all the heavy items out of his backpack. This is what we are trying to do with prefabrication for the bottlenecked trade partners.

Finish As You Go – No Go-Backs, Punch Lists, or Loose Ends

We tend to start activities with traditional management methods because our CPM tells us to, or to show external stakeholders that we are ‘on schedule.’ Our teams are allowed to bill for progress that they have made, thus incentivizing this errant behavior. Adding work in progress only exacerbates the issues as now we have more potential for defective work, and management is stretched out, covering the more frequent problems arising. We do not finish the same work, leaving lots of hanging threads all over the project, and we will need to stop the flow of work to go back to complete these areas. This mode of operating can have negative effects, as we have discussed in previous chapters.

Adam recalls when he learned this the hard way. On a 220,000 SF dorm and dining facility at Clemson University. There were areas of work that started all over the building, causing chaos and confusion about the project’s status. When the decision was made to stop starting work and start finishing work, the project made a substantial leap forward. Seeing this in real-time helped convince the team they should always obey production laws. Further understanding of Little’s Law and the law of variation have proven this to be the reason why the turnaround was so remarkable. The decision to focus on finishing smaller batches was the best thing for the project.

Own Your Zone

As we discussed when starting your Takt planning, the project will be broken into different Takt zones, and trades will systematically move their way through each zone to completion. The team must all agree on what the handoff of a Takt zone is defined as, meaning when a zone is handed over to you, you “own” that zone. This means that everything that happens in that Takt zone is the Zone Owners’ responsibility, and that trade partner will be held accountable to ensure the next wagon receives a workable Takt zone. This also means the team will respect the other zones turned over to the other trades. Here is what it means to own the zone:

- Cleanliness – Accountable to ensure the level of cleanliness is the same or better during their zone own and turnover.

- Safety – Accountable to ensure all safety hazards within each zone has been mitigated appropriately during their zone own and turnover.

- Defective (Damaged) work – Accountable to inform trade partners and/or repair damaged or defective work during their zone own and turnover.

- Finishing work – Accountable to finish their work within the Takt zone in the proper Takt time.

The handoff points become more important as we encourage teams to work together to hand off the zone and/or accept the next zone. Ensuring clear conditions of satisfaction are vital to promoting flow from Takt zone to Takt zone. Zone acceptance inspections become critical to understand the current conditions before taking ownership of a Takt zone. As progress continues, we enable trade partners to get a Takt zone ownership flag and move their flag with them. This visual representation is telling the world that this zone is owned and by who. Think about the amount of pride and ownership that this philosophy is encouraging at the project site level.

If flow is to continue, accountability must be paramount to all parties involved. While planning for proper production on site is the first step, executing the work is the next. The team needs to be aware of the plan and hold each other accountable for producing as expected. The practices described in this post serve as a starting point for you to develop a culture on your jobsite where the work is continually flowing and the project is owned.

Chapter 15: Stop in the Name of Production Management

When making improvements, we tend to focus on adding new structures or practices to our daily routines. We don’t look enough at practices that we are already doing and what we could stop. Often, this can make just as large of an improvement as adding something new. Many of our common practices today do more harm to our projects than we realize. When it comes to Project Production Management and using Takt, these practices directly oppose the production laws.

Stop Starting Work That Isn’t ‘ready’

How often have you been in a weekly planning meeting when someone is told that they need to start work in an area because “the schedule says we should be here?” The chances are that this happens quite often. Teams look at this as a way to push trades falling behind or get a new trade onto the job as soon as possible. It is also a regular practice to measure the percentage of planned activities started per the master schedule. We need to STOP doing this.

We have discussed the idea of making work ready throughout this series. This is an absolute MUST before starting work. If we continue to start work that is not ready, it will add unnecessary Work in Process (WIP) to our system and make everything take longer. On top of that, we know that speeding up trades who are not the bottleneck will do nothing to speed up the project as a whole. It might end up slowing us down if the work they are putting in place will be in the way for someone else. The weekly make-ready process with the team is crucial for all parties to understand what is ready to be started and what is not. Sometimes the project overall should hold off on starting work.

Stop Planning to 100% Capacity

If we are paying for resources (people or equipment), we want to make sure they are working. Because of this, we generally plan crews to work at 100% of their capacity when they are on the jobsite. While this does make sense in some respects, it leaves us vulnerable to the inevitable variation that will come our way. If everyone is working at 100% capacity, we need to pull them from their planned work to address the change. This leaves work needed for other trades unfinished, which can send ripples through the entire project.

This is where a properly managed capacity buffer solves our problem. Having additional crew members working specifically on workable backlog allows them to be pulled in to address variation when needed. This gives us the best of both worlds. Everyone will be working on value-added work, but we will also handle the variation when it happens. The key is planning for this from the start.

Stop Operating with a ‘Plan of the Day’ Mentality

If you have ever spent time working around a design or construction project, you would probably agree that “firefighter” could be added to your resume. It is very common to hear folks describe the scenario where, based on something that happened yesterday, they need to redirect the crews in the morning to address the issue. Too often, we will fall into the habit of operating on this “plan of the day” routine and find ourselves in a complete reactionary mode. This has a significant impact on the productivity of crews, not to mention the effect of changing plans every day will have on the overall project. Introducing more variation to the plan never has good results.

Working within a proper set of buffers can help with this. If there is standby capacity, it can take care of the issues that arose, as discussed earlier. Additionally, having a workable backlog can give crews somewhere to go if the problem area requires some replanning and work to stop. The key is to approach the issue as a team and plan for the solution. We want to keep work flowing and steady. Ensure that the work that needs to be done to maintain the overall flow is held as the priority.

This deep dive has introduced you to the fundamental science behind Project Production Management, Takt planning and control, and a number of practices that you can start doing and some practices to avoid. The field of Project Production Management is far broader than we have covered in this e-book. But we hope it can all serve as a small primer to begin researching on your own and discover how PPM can significantly improve your project results.