(By Hal Macomber and George Hunt, Lead – Pre-Sales/Sales Engineering Touchplan) We’ve learned not to ignore production laws when we plan our projects. There is one approach that we should all be starting with as we plan. It’s takt, a German word borrowed by the Japanese, meaning beat, rhythm, or pace. The intent is to establish a consistent rate for performing all operations for a work phase. Ideally, the speed is set based on the desired milestone completion for the phase and project.

Pacing production brings the four production laws together.

- A constant pace removes variation.

- We set the pace based on the smallest practical batch of work.

- The bottleneck operation(s) will control the pace.

- We avoid delays resulting from high capacity utilization and variation.

Pacing production has been a central idea in the Lean construction community since 1999 when Dr. Iris D. Tommelein, Director of the Project Production Systems Laboratory, UC Berkely, authored a white paper for the Lean Construction Institute. In February 2020, at the annual Design Forum, Iris declared,

“Takt planning applies to all projects.

No exceptions including non-repetitive (sequential) work.”

Not only do we agree with Iris, but Hal’s been using takt on projects since 1999. We haven’t seen any evidence to hint at an exception to Iris’s rule. Furthermore, takt, under different names, has been used at least as far back as the construction of the Empire State Building, which only took 13½ months to complete.

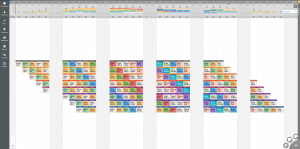

We will explore takt in-depth in the next eight blog posts. Takt plans look like this.

Notice the stair-step approach. You saw that in the blog post on batch sizing. When setting the takt time (pace), we start with one day to get the shortest phase plan. One day may not be possible for all operations in a phase plan without making accommodations. For example, teams may need to examine the steps in their process to distinguish what is value-adding and necessary to perform at the installation location. All other work steps are candidates for moving offline. For instance,

- Don’t unpackage material at the work site if someone could do that beforehand.

- Don’t mobilize and demobilize tools and materials if they can be on a cart that moves with the workers as they go from one flow unit to another.

- Don’t measure, cut, assemble and coat in the workspace if that could be moved off-site.

The aim for achieving flow is to install, install, and install. Remember, this matters most for those operations that exceed the desired takt — the bottlenecks.

The usual ways trades work may not be conducive to a consistent short takt. The way we contract the trades contributes to that. While balanced work is essential, we often contract with one trade without considering the desired paces of the work phases. Remembering that flow is our goal, we must make a fundamental shift from my work to our work. It’s a shift that starts with treating the performers of the next operation as “my customer.” And, it requires that I respect the performers’ work that came before me. It is not hard to do. In too many situations, we just aren’t trying to do it.

We get the best results from prefabrication or offsite construction when making those decisions early in the project’s design. Takt is similar. Have a workshop with key trades during preconstruction to collaboratively explore the opportunities for pacing.

Two days ago, George and Hal taught an “Introduction to Takt Planning and Control, Making the most of your Last Planner System® Projects” for the LCI New England Community of Practice. We will teach it again later this summer and at the LCI Annual Lean Design and Construction Congress in Phoenix in October.

If you missed our last blog, be sure to read Flow When you Can – Pull When you Can’t – Stop Pushing, and for more information on Lean planning check out Skip the Stickies and Learn LPS Digitally.