(By Hal Macomber and Colin Milberg, Principal ASKM Associates)

Our common sense tells us the more work we get started then the sooner we finish. One common practice is to give a framer a whole floor of a building thinking that makes them more productive. We think productivity is equivalent to speed. It’s not.

Professor John Little, Ph.D., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, did the proof (Little’s Law) that relates time in a system (like the time to complete all steps on a floor) with processing time (like the speed crews complete a floor) and the internal arrival of work (like the amount of floor space started but not finished). The implication for construction is that the more frequently we hand over space from one trade to the next, i.e., the less stagger between trades, the sooner the project will finish.

It is our moral imperative to design our construction production process to our smallest practical batch sizes. Otherwise, we are squandering our client’s resources. And … we reduce our risk in the process.

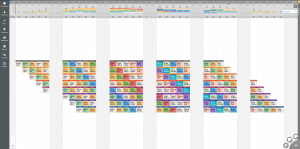

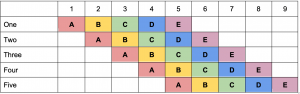

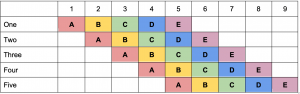

Let’s use a simple example. We have a small project. There are five floors in the building. Five operations need to be done on each floor by five different trades. Each trade is staffed to do their work on a floor in five days. We’ll start with the situation where each trade hands off a floor each week. The first trade A finishes floor 1 on week 1 and then moves to floor 2 at the beginning of week 2. That makes floor 1 available for trade B on week two. By week 5, trade A is working on the fifth floor, and trade E starts on the first floor. Week-by-week each trade moves up the building finishing their work in five weeks. Trade A finishes in the fifth week. Trade E finishes four weeks later in week nine.

Now let’s consider how long the project would take if we hand over 20% of the floor each day. On day two the 2nd trade starts, and by day 5 all trades are working which is more than three weeks earlier than the above larger handoff or batch approach. When the handoff or batch size is a whole floor it takes nine weeks. When the batch size is cut to 20% of the floor it takes 29 days cutting the time by 35%!

Calculating the Benefit of Small Batch Production

We derive an equation for determining the duration of a phase of work from Little’s Law. In the following equation [ Work In Process] / Throughput = Cycle Time, where: Work In Process is the maximum number of areas or flow units being worked on in a given moment; Throughput is the speed of the crews shown as the number of areas in a batch divided by the time required for a crew to complete the batch, and Cycle Time is the amount of time for all operations to complete one area.

[(Number of Flow Units – Batch Size) + (Number of Operations * Batch Size)] / Throughput = Total Project Duration.

First, let’s use the above example. There are 25 flow units (work areas that can be started and finished). In the first case, a trade does a batch of five flow units before turning over space to another trade. There are five operations (trades) performed on each flow unit. The throughput time (the time the flow unit is in an operation) is 5 flow units in 5 days or 1 unit per day.

One week stagger [(25 – 5)) + (5 * 5)] * 1 / 1 = 45 days

One day stagger [(25 – 1)) + (5 * 1)] * 1 / 1 = 29 days

Savings 16 days, about 35% shorter!

Second case: 18-story university residence hall, alternate floors had different layouts. The work involved interior framing through finishing. There were 26 operations. We proposed splitting into two flow units per floor with different layouts, but similar square footage. The GC planned to turn over one floor per week (5 days). We proposed to turn over one flow unit (half-floor) every two days. Notice the flow units increase because we made the space smaller.

One week stagger [(18 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 5 / 1 = 215 days

Two day stagger [(36 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 2 / 1 = 122 days

Savings: 93 days, about 43% shorter!

Let’s consider going smaller, then smaller again. First ¼ of a floor, then ⅛.

One day stagger [(72 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 1 / 1 = 97 days (doubled the flow units)

Savings: 25 days, about 20% shorter!

Half day stagger [(144 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 0.5 / 1 = 84.5 days (doubled the flow units, again)

Savings: 12.5 days, about 13% shorter!

Quarter day stagger [(288 – 1) + (26 * 1)] * 0.25 / 1 = 78.5 days (doubled the flow units, again)

Savings: 6 days, about 7% shorter!

The time savings from the change in batching from 18 flow units to 288 flow units resulted in savings from 215 days to 78.5 days. A whopping 63% reduction in the cycle time!

Think about this …

How much money can we save for our clients when we significantly reduce project durations?

How much revenue or value can we produce for our clients when we deliver projects earlier?

It is our moral imperative to design our construction production process to our smallest practical batch sizes. Otherwise, we are squandering our client’s resources. And … we reduce our risk in the process.

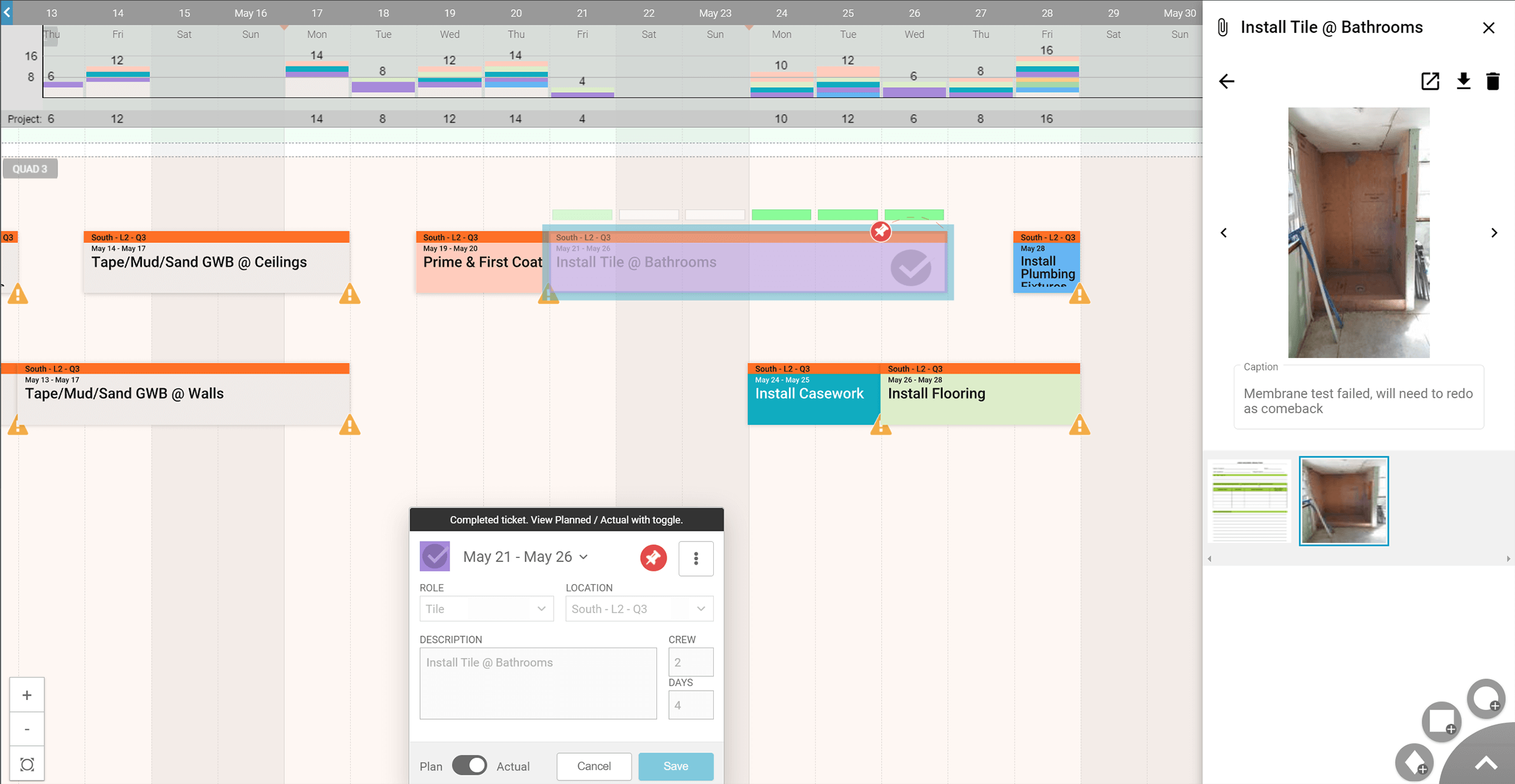

Implications for Phase Planning

Projects take more time the larger the batch of work in a physical area that is exclusively assigned. Cut the batch size and the project will get shorter as long as the workflows without interruption from one trade to the next. Notice there is a diminishing return as you continue to cut batch size.

We use a rule of thumb to start with a batch size that can be done reliably by all trades in one day. Scale up the number of flow units from that if necessary to accommodate crew sizing. We’ll cover more on this in upcoming blog posts.

Not only are projects shorter with small batches but quality, safety, and workplace cleanliness improve. Of course, all of this depends on being able to execute the plan. Initially, there will be bumps in the road. Commit yourselves to learn from mistakes and the project will get better fast.

Connect with Colin on LinkedIn

If you missed last week’s post please check out Delays Increase Exponentially as Utilization Increases. For additional insights on Project Production Management please read Takt Time Planning and Laws of Production: Getting the Most out of LPS.